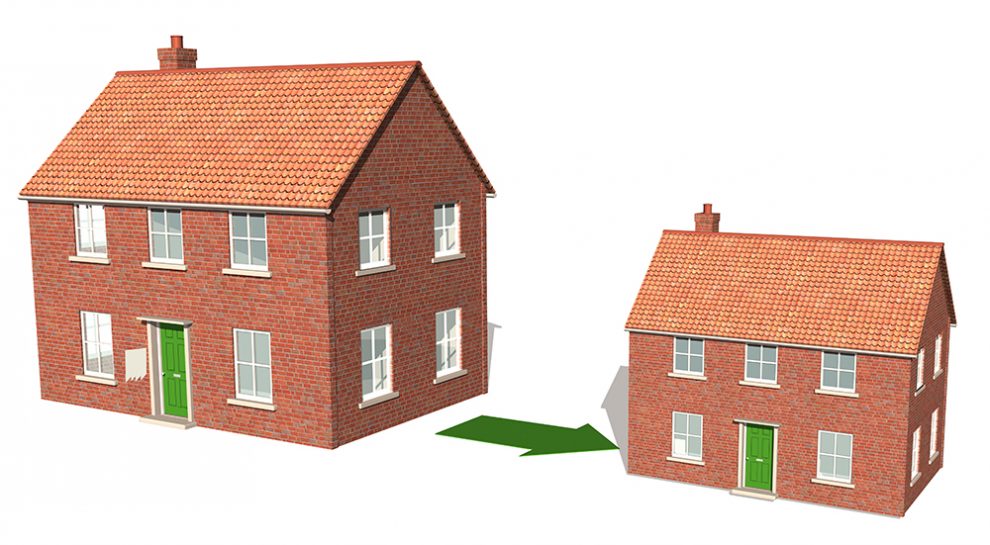

It’s time to debunk the myth of zero housing costs in retirement if we want to understand why retirees resist downsizing. Retirees have at least five reasons to be wary of the costs of downsizing, writes Erika Altmann, University of Tasmania.

Retirees living in middle-ring suburbs face frequent calls to downsize into apartments to free up larger allotments in these suburbs for redevelopment. Retirees who fail to downsize into smaller units and apartments are viewed as being a greedy, baby-boomer elite, stealing financial security from younger generations.

It also makes sense to policymakers for retirees to move into less spacious accommodation and make way for high-density housing. Housing think-tank AHURI fosters this view. Yet seniors remain resistant to moving, in part because of the ongoing costs they would face.

The concept of zero housing costs in retirement is based on a 1940s view of a well-maintained, single dwelling on a single allotment of land where the mortgage has been paid off. This concept is incompatible with medium- and high-density housing and refusing to acknowledge ongoing housing costs may cause significant poverty for retirees.

Reason 1 – upfront moving costs are high

When a house is sold the owner receives the sale funds minus the real estate and legal fees. When the same person then buys a different property to live in, they pay legal fees plus stamp duty.

For cities such as Melbourne and Sydney, these costs are likely to exceed A$70,000.

These high transfer costs may mean it is not cost-effective for the person to move.

Reason 2 – levies are high

Because apartment owners pay body corporate levies, people often assume this is just the same as periodic payment of rates, water, insurance and other costs. It is not.

Fees remissions for low-income retirees for rates, power, insurance and water are difficult to apply within a body corporate environment. As a consequence, these are usually not applied to owners of apartments.

The costs of maintaining essential services, such as mandatory fire-alarm testing, yearly engineering certification, lift and air-conditioning inspections, significantly increase ownership costs.

When additional services are supplied, such as swimming pools, gyms and rooftop gardens, these also require periodic inspections. Garbage collection, cleaning, gardening, concierge and strata management services also must be paid.

Owners of standard suburban homes choose whether they want these services, with those on fixed incomes going without them.

Annual levies for apartment buildings vary, but expect to pay between $10,000 and $15,000. They may be more than this.

Reason 3 – costs of maintenance

Apartments are often sold as a maintenance-free solution for older people. The maintenance is not free. It needs to be paid for.

Maintenance costs are higher in an apartment than a standard suburban home because there are more items and services to be maintained and fixed. Lifts and air conditioning need periodic servicing and fixing. This is in addition to the mandatory inspections listed above.

Reason 4 – loss of financial security

It is a mistaken belief that the maintenance costs that form part of the body corporate fee include periodic property upgrades. This relates to items that are owned collectively with other apartment owners.

Major servicing at the ten-year mark and usually each five-to-seven years after that include painting, floor-covering replacement, and lift and air-conditioning repair or replacement.

Major upgrades may also include garden redesign or other external building enhancement including environmental upgrades. All owners share these upgrade costs.

Costs of upgrading the inside of an apartment (a bathroom disability upgrade, for example) are additional again.

Once the body corporate committee members pledge funds towards an upgrade, all owners are required to raise their share of the funds, whether they can afford it or not. Communal choice outweighs an individual owner’s need to delay upgrade costs.

Owners who buy apartments that are part of a body corporate effectively lose control of their future financial decisions.

Reason 5 – loss of security of tenure

Loss of security of tenure is usually associated with renters. However, the recent introduction of termination legislation in New South Wales gives other owners the right to vote to terminate a strata title scheme. When this occurs, all owners, including reluctant owners of apartments within that scheme, are compelled to sell.

There are valid reasons why termination legislation is desirable, as many older apartment complexes are reaching the end of their useful life.

Even so, as termination legislation is rolled out across the states, owner- occupiers effectively lose control of how long they will own a property for. They no longer have security of tenure, which means retirees may face an uncertain housing future in their old age.

Downsizing raises poverty risks

Because current data sets do not adequately take account of ongoing costs associated with apartment living, the effect of downsizing on individual households is masked.

Downsizing retirees into the apartment sector creates ongoing financial stress for older people. Creating tax incentives to move does not tackle these ongoing costs.

Centrelink payments for of $404 per week are well below the poverty line. Yet we expect retirees to willingly downsize and to be able to cede most of their Centrelink payments to cover high body corporate costs.

Requiring retirees to downsize for the greater urban good will shift poverty onto retirees who could barely manage in their previously owned standard suburban home.

Failing to understand the effect of high ongoing costs associated with apartment living and reinforcing the myth of zero housing costs in retirement will continue to lead to poor policy outcomes.

ABOUT

Erika Altmann, Property and Housing Management Researcher, University of Tasmania

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Add Comment